I never thought much about Italy’s experience in the First World War. What I knew about it was an offhand remark from the narrator of The Sun Also Rises, who was emasculated on “a joke front like the Italian”. I knew Erwin Rommel had first come to glory there, putting into practice the theories of warfare that would drive German success early in World War Two, at a time before those theories had even crystallized. And I knew that Italy performed in-line with jokes about its military incompetence..

But it turns out there is a remarkable and important story to be told about the Italian front. I only happened on it by chance in the remaindered section of the Harvard Bookstore, where I picked up a copy of Mark Thompson’s The White War for $5, after it had likely sat ignored on the history shelves in the same way that “history buffs” like me tend to ignore its subject matter.

In the main, Thompson’s book fulfills its most important obligation: it tells an interesting and unfamiliar story, and it tells it very well. The White War is stocked with scarcely believable characters, like the proto-Fascist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, who styled himself as the poet laureate of the Italian right and was basically allowed to treat the battlefield as a kind of muse-for-hire. One day he is seen giving pep talks to headquarters staff, the next he is flying over Austrian lines, dropping propaganda leaflets. The next time he pops up, he is arranging some kind of absurd raid to capture a distant castle and raise the Italian flag over its ramparts, thereby boosting morale across the entire front.

In a way, a character like D’Annunzio is laughable, and stereotypically Italian. Look at him bluster, look at his vainglory. Look at this failure.

But the horror of Thompson’s book is that millions of men and women were caught up in this joke, and at the mercy of the pure viciousness that lay behind the strutting vainglory. As the Italian raid on the Austrian castle fell apart at a river crossing, under heavy Austrian fire, stranded Italian troops began advancing toward the Austrians to surrender. D’Annunzio, watching from across the river, was disgusted by their “cowardice” and orders the artillery to execute a fire mission against the Italian “traitors”. And such was the poet’s power in this Italian army that the batteries did indeed open fire and on the victims of D’Annunzio’s own folly.

But all that pales next to the character of Luigi Cadorna, a general whose name I had never heard prior to this book.

Discovering Cadorna and his place in the annals of history’s worst commanders is like discovering there is an extra planet in the solar system that nobody ever mentions. He’s so profoundly awful, as a general and as a human being, that the mind reels.

In fact, The White War warms to its task as Thompson really begins dissecting Cadorna’s record, and shifts focus from the front lines to the rear echelons and headquarters. Cadorna revealed himself to be an ineffectual martinet in the opening stages of the war, as he squandered massive opportunities and then, for good measure, squandered immense numbers of lives trying to crack impregnable Austrian positions across the Alps. Yet he was so arrogant, and so coddled by an Italian government that feared his prestige, that he was neither shaken by his failures nor fearful of their consequences.

But as the war dragged on, Cadorna’s lack of accountability and belief in iron discipline began going to darker and darker places, and Thompson follows right along. Cadorna, so contemptuous of the soldiers he was charged with leading, became convinced that Italian setbacks were due to poor morale, poor discipline, and outright cowardice.

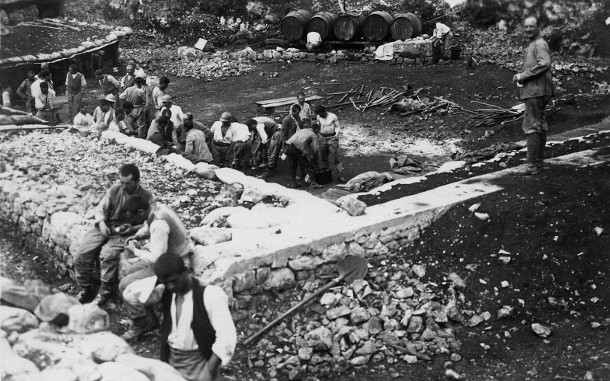

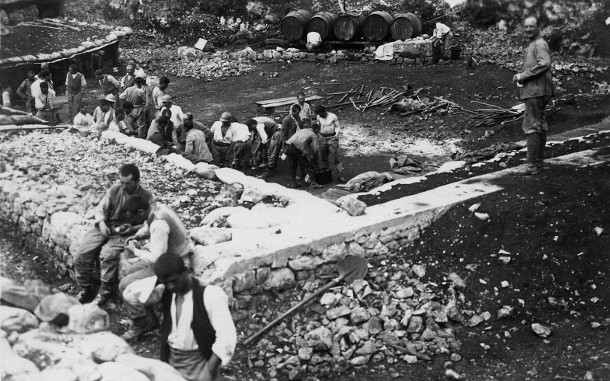

His solution, at first, was limited to trying to remake the Italian soldiery in his image: ascetic, hard-working, and fanatically dedicated to duty. Soldiers barely received any leave and, on the rare occasions their units were rotated off the front lines, they were sent not for R&R but for hard-labor behind the lines, lest they become soft. The theory was that soldiers should greet their return to the front with zeal and relief, and go about each day without a thought of home and peacetime pursuits.

But as years of hopeless slaughter took their toll (Thompson’s descriptions of combat along the varied and universally forbidding terrain of the Austro-Italian border are frequently jaw-dropping, like when he describes Italian “lines” where soldiers were living in tents anchored to cliff faces), the Italian troops became increasingly hopeless and their performance seemingly declined. There were more instances of indiscipline and routing.

Cadorna escalated matters, taking a “the beatings will continue until morale improves” approach, instituting an entirely extralegal regime of summary executions for all manner of infractions, to be pursued at the discretion of officers in the field. Courts martial, he decided, were too lenient for the weak, slovenly Italian army. He openly called it a policy of decimation.

The incidents Thompson brings to light are shocking. Cadorna is a real-life version of General Broulard in Paths of Glory, only far worse than even Stanley Kubrick could plausibly make out. Under his regime, subordinate commanders began looking for reasons to execute soldiers, so that they could demonstrate their fealty and zeal to the generalissimo’s vision.

In one gut-twisting example, Italy’s Ravenna Brigade “mutinies” when it discovers it is being sent back to the line after only a short respite. A few drunk soldiers fire guns in the air, and many soldiers refuse to go. Then the assistant division commander and brigade CO hear out the men’s grievances, summon military police to restore order, and pack the brigade on its way.

Except the division commander and eventually the corps commander get wind of the incident and began demanding executions. First a handful of men are shot and then, as each higher-ranking officer hears of the incident, ever more executions are demanded. In the end, Thompson writes, “29 men died to punish a minor rebellion in one battalion that lasted a few hours, causing no casualties.” (p. 265)

This is just one, unusually well-documented example, Thompson writes. The actual death toll for Cadorna’s summary executions goes as high as 750, if not higher.

Months later, in the autumn of 1917, Cadorna was stunned when a joint German-Austrian offensive hammered his lines at Caporetto and his army collapsed, with entire formations refusing to obey his order to fight to the death.

The Undertow of Progress

This would all make for a riveting account of a disastrous military campaign, but what elevates The White War is Thompson’s broader interest in Italian politics and culture. Cadorna as a general is a villain. But Cadorna’s absolute authority in Italy, his aimless brutality…. all these are harbingers of what is to come.

Over the course of The White War, Thompson shows the seeds of Fascism taking root in a soil rich with political, social, and cultural dysfunction. Italy, a young state in 1915, immediately began drifting toward militaristic hyper-nationalism and authoritarianism as soon as war was declared. The press was promptly muzzled, and happily went along with the policy of official censorship. Civilians were denounced and jailed for defeatism and lack of patriotism. Italy would not become formally fascist until 1924, but its slide in that direction started early in the war.

This had real consequences during the war and lent Italy’s ultimate victory a toxic legacy. There were always more delusions and excuses that enabled Cadorna’s mismanagement of the war. Socialist agitators sapped the soldiers of their will to fight. Italy’s allies weren’t helping enough. Unpatriotic politicians were shaking the army’s belief in itself every time they raised questions about the campaign. The soldiers were weak, lazy, ignorant who broke faith when victory was at hand. Each of these stories became a part of the right-wing’s founding myth of fascist Italy.

Cadorna himself was called “Il Duce” long before Mussolini (who lurks at the margins of his narrative, a minor player in the unfolding political drama, and not yet sure of his own beliefs). He was actively indulgent of suggestions that he be made dictator. Cocooned by a restricted press that parroted his own propaganda back at him, and a quiescent general staff that had been conditioned to flattery and mimicry, Cadorna became convinced of these “facts” that he’d helped invent.

Thompson also shows how Cadorna’s mindless credos, his oft-disproven and oft-repeated belief in the power of the offensive and the “irresistible spirit” of a good army, had their underpinnings in a widely-shared, somewhat incoherent set of beliefs called vitalism, which valued intuition personal character over intellect or material goods. In an insightful and important passage that helps explain the entire era, he writes:

“Vitalism appealed to the anti-intellectual bent of intellectuals who already doubted the rationalist rules of their game. Trapped in the vast dynamics of nationalism, imperialism, militarism, industrialisation and commerce, and by the theories of natural evolution, human history and the unconscious mind discovered by Darwin, Marx and Freud, what room was left for individual reason and moral will? How should men not succumb to the dark currents running below Progress (justly called ‘the political principle of the nineteenth century’), namely a gnawing sense of degeneration and impotence, merging fear of technology with fear of women? In hindsight, vitalism was a resistance movement, a late-romantic defence of the individual male and his solitary resources, a consolation after the ‘death of God’ in the mid-nineteenth century and before the birth of ‘human rights’ after 1945. For the vitalist vision is self-deifying, promising to restore mankind to his rightful place in the scheme of things, able to master all species and materials through mystical life-force.” (p. 229-230)

This is a passage that immediately helps crystallize a lot of the thinking that went into World War I, and even more of what came out of it. It’s fascinating that the Italian Front provides such a perfect window into the 20th century, in Thompson’s telling.

The ultimate tragedy of The White War, beyond all the lives lost, is that Thompson convincingly demonstrates that this incoherent mix of self-loathing and denial never really left Italy. Italy, a young country at the time of World War 1, was traumatized by its monumental failures against the Austrians. It promoted the idea that Italy itself was broken and needed to be fixed, and Fascism took advantage of that impulse when it sought to rehabilitate the war and sell it as a “founding myth” of Mussolini’s fledgling empire. When that was discredited, the self-doubt crept back into Italian politics.

In Thompson’s view, Italy is stuck with the memory of Caporetto, and the sudden disintegration of their army, their confidence, their view of themselves as a nation. In one form or another, the Italian front unleashed forces and beliefs that have twisted Italian politics ever since.